Critically ill children with prolonged lengths of stay, central venous catheterization, and concurrent infectious or parainflammatory processes have a high risk of hospital‐acquired venous thromboembolism (HA‐VTE).1,2

Read the source article for this feature from

Pediatric Critical Care Medicine.

But no randomized controlled trials have evaluated thromboprophylaxis in critically ill children. Anticoagulation therapy is not routinely prescribed for critically ill children and adolescents, as it is for hospitalized adults.

3,4

“Blood clots are the second most common hospital-acquired condition in children next to bloodstream infections,”

5 said Anthony A. Sochet, MD, a pediatric intensivist at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida, USA, and associate professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “That’s actually somewhat understated anecdotally, in the sense that the prevention of blood clots is not on the forefront of the minds of most intensivists who are working with children.”

Dr. Sochet and colleagues are working on producing trial-derived data for children, aiming to prevent HA-VTE. His latest findings were published in the September 2025 issue of

Pediatric Critical Care Medicine.

6

Currently, thromboprophylaxis use in children is based only on observational studies and anecdotal evidence. Dr. Sochet suspects that many clinicians try mechanical or nonpharmacological thromboprophylaxis (compression devices) first.

3,4,7,8 “These devices are thought to work by squeezing your veins and, as a result, improving blood flow when you’re immobilized, reducing that potentially prothrombotic state,” he explained. “But there are some other beliefs too—and I say ‘beliefs’ because they’re not proven—that when you squeeze a vein, the cells that line the inside of the vein release endogenous anticoagulants into the bloodstream.

9-12 We apply mechanical thromboprophylaxis in children and we have no idea if it’s efficacious and it may be distracting from measures like anticoagulants that are actually effective.”

The Findings

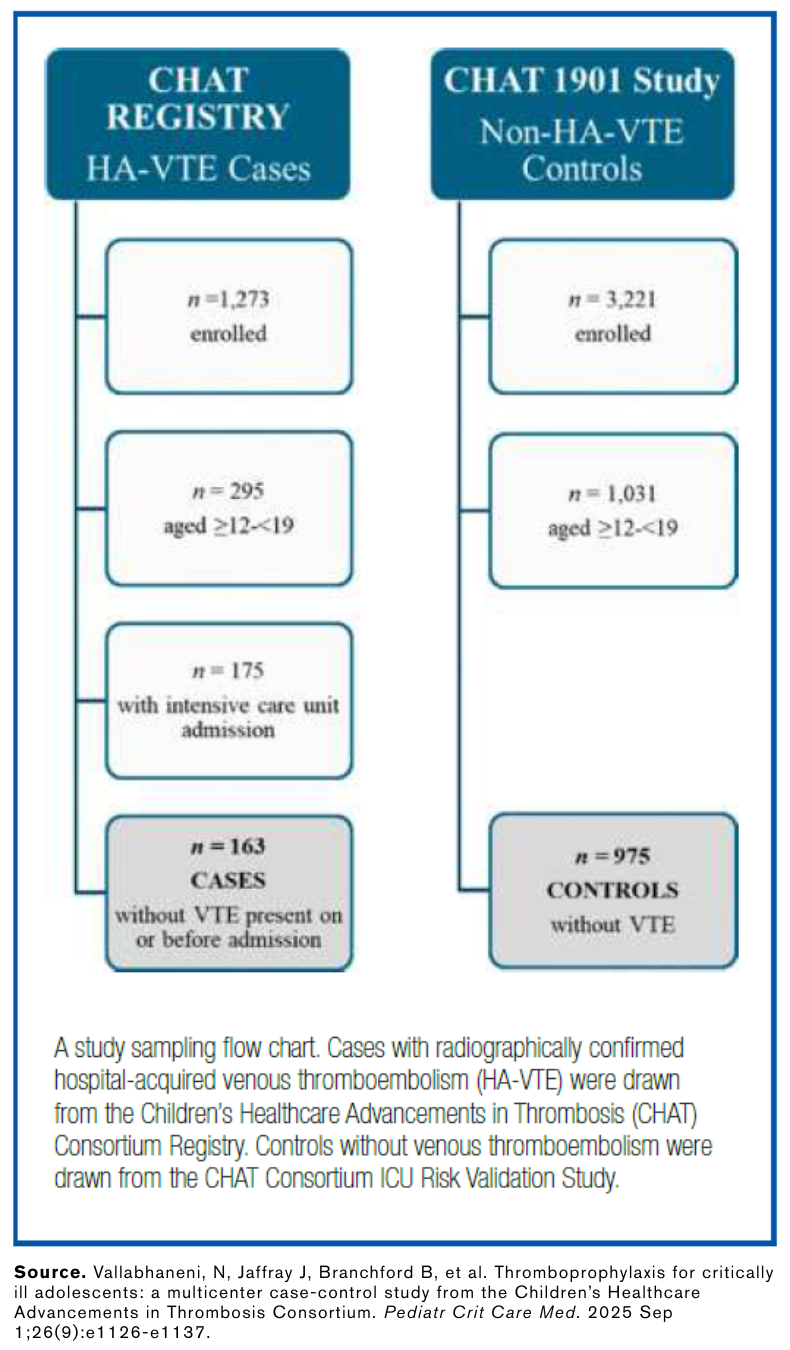

Dr. Sochet and the research team conducted a multicenter case-control study within the Children’s Healthcare Advancements in Thrombosis (CHAT) Consortium Registry and CHAT VTE risk-model validation study. They studied critically ill adolescents aged 12 to 19 from 32 North American pediatric intensive care units. They compared 163 patients with radiographically confirmed HA-VTE to 975 controls without HA-VTE. Compared with controls, patients with HA-VTE more frequently had central venous catheterization, invasive ventilation, longer median length of stay, impaired mobility, and infection.

Dr. Sochet said that younger children were not included in the study because adolescents are more likely to be prescribed compression devices with or without an anticoagulant and adolescents have higher rates of HA-VTE than other pediatric age groups.

13,14

The researchers grouped the patients into predefined low, medium, and high risk of developing a VTE.

1 The study found that the only therapy that prevented HA-VTE in all three risk groups was anticoagulants. The risk was lower in those who received pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis alone or in combination with mechanical thromboprophylaxis but not in those who received only mechanical thromboprophylaxis.

Dr. Sochet said of the study findings, “It may be that we are distracting ourselves in using mechanical thromboprophylaxis—because clinicians worried about bleeding risk sometimes say, ‘Oh, you know what, I’ll just apply mechanical thromboprophylaxis instead so that they don’t have a risk of bleeding and I get the same bang for the buck for preventing VTE.’ But the truth is, it’s more likely that we don’t actually prevent VTE with mechanical thromboprophylaxis and that we need to, instead, more proactively apply pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.”

What’s Next

These findings could also apply to young adults, Dr. Sochet said. He noted that it is common in pediatrics to say that adolescents are not the same as young adults when it comes to treatments but, with blood clots, adults in their 20s and 30s are probably more similar to adolescents than to older patients. Most anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis studies in adults exclude people younger than 40 years and typically have a median age in the 60s.

15-17 “When we try to extrapolate those trial data [on older patients] to people who are 20 to 25, we’re probably doing them a disservice because they’re more like children than they are like adults. This study probably is applicable to young adults who are also critically ill—and maybe more applicable than any of the adult data thus far.”