2015 Choosing Wisely Recommendations

Download Now

Download Now

Read the Article in Critical Care Medicine

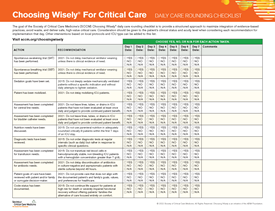

1. Don’t order diagnostic tests at regular intervals (such as every day), but rather in response to specific clinical questions.

Many diagnostic studies (including chest radiographs, arterial blood gases, blood chemistries and counts and electrocardiograms) are ordered at regular intervals (e.g., daily). Compared with a practice of ordering tests only to help answer clinical questions, or when doing so will affect management, the routine ordering of tests increases health care costs, does not benefit patients and may in fact harm them. Potential harms include anemia due to unnecessary phlebotomy, which may necessitate risky and costly transfusion, and the aggressive work-up of incidental and non-pathological results found on routine studies.

2. Don’t transfuse red blood cells in hemodynamically stable, non-bleeding ICU patients with a hemoglobin concentration greater than 7 g/dL.

Most red blood cell transfusions in the ICU are for benign anemia rather than acute bleeding that causes hemodynamic compromise. For all patient populations in which it has been studied, transfusing red blood cells at a threshold of 7 g/dL is associated with similar or improved survival, fewer complications and reduced costs compared to higher transfusion triggers. More aggressive transfusion may also limit the availability of a scarce resource. It is possible that different thresholds may be appropriate in patients with acute coronary syndromes, although most observational studies suggest harms of aggressive transfusion even among such patients.

3. Don’t delay providing nutrition, preferring enteral over parenteral, to critically ill patients during the first 24–36 hours of a critical illness.

Two large multicenter trials compared early (within 24-36 hours of ICU admission) enteral nutrition with parenteral nutrition and clinical outcomes related to mortality (30-day, ICU, hospital and 90-day), length of stay (ICU and hospital), and infections (pneumonia and bacteremia) were not significantly different. Based on more recent, higher quality data, parenteral nutrition should not be avoided regardless of nutrition risk.

4. Don’t deeply sedate mechanically ventilated patients without a specific indication and without daily attempts to lighten sedation.

Many mechanically ventilated ICU patients are deeply sedated as a routine practice despite evidence that using less sedation reduces the duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU and hospital length of stay. Several protocol-based approaches can safely limit deep sedation, including the explicit titration of sedation to the lightest effective level, the preferential administration of analgesic medications prior to initiating anxiolytics and the performance of daily interruptions of sedation in appropriately selected patients receiving continuous sedative infusions. Although combining these approaches may not improve outcomes compared to one approach alone, each has been shown to improve patient outcomes compared with approaches that provide deeper sedation for ventilated patients.

5. Don’t continue life support for patients at high risk for death or severely impaired functional recovery without offering patients and their families the alternative of care focused entirely on comfort.

Patients and their families often value the avoidance of prolonged dependence on life support. However, many of these patients receive aggressive life-sustaining therapies, in part due to clinicians’ failures to elicit patients’ values and goals, and to provide patient-centered recommendations. Routinely engaging high-risk patients and their surrogate decision makers in discussions about the option of forgoing life-sustaining therapies may promote patients’ and families’ values, improve the quality of dying and reduce family distress and bereavement. Even among patients pursuing life-sustaining therapy, initiating palliative care simultaneously with ongoing disease-focused therapy may be beneficial.