As an update to a 2019 workforce report, three committees from the Society of Critical Care Medicine evaluated critical care medicine’s continued emergence from the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in the critical care workforce, and pitfalls exposed by the pandemic.

The landscape of critical care practice continues to change, but the multiprofessional team approach remains the foundation of delivering high-quality critical care medicine. As an update to a workforce report published in

Critical Connections in 2019,

1 three committees from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) evaluated the field’s continued emergence from the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in the critical care workforce, and pitfalls exposed by the pandemic. This update will cover critical care training across multiple professions including physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and respiratory therapists (RTs) and will showcase efforts to promote and increase the number of practitioners available in critical care medicine.

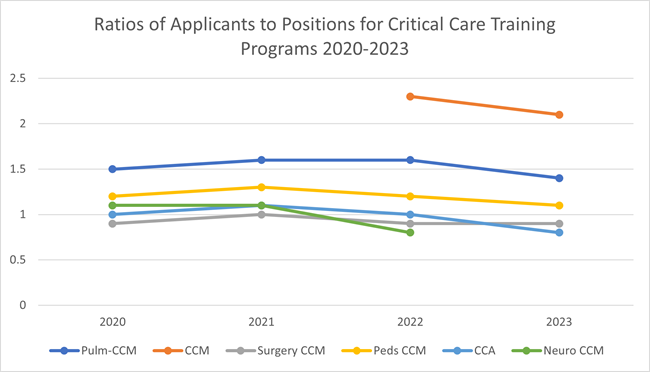

Growth in Graduate Medical Education Positions

As the need for critical care physicians continues to increase, the ability to train qualified physicians will need to rise to meet the demand. Data compiled from both the National Residency Match Program and the SF Match have shown increases in programs offering training positions in critical care medicine (

Figure 1).

2,3 Critical care medicine is now also offered as a stand-alone training program, highlighting the field’s importance as a clinical specialty by not requiring previous residency training in areas such as internal medicine, emergency medicine, anesthesiology, pediatrics, or general surgery.

|

Figure 1: Comparison of Training Programs Across All Pathways of Critical Care Training

CCA, critical care anesthesiology; CCM, critical care medicine.

Data compiled from National Resident Matching Program2 and SF Match.3

|

Traditional pathways of residency-to-fellowship programs remain the most common method for trainees to enter critical care medicine training, but those entering from other fellowship programs such as cardiology, nephrology, and infectious diseases should help to increase the number of critical care physicians in the United States.

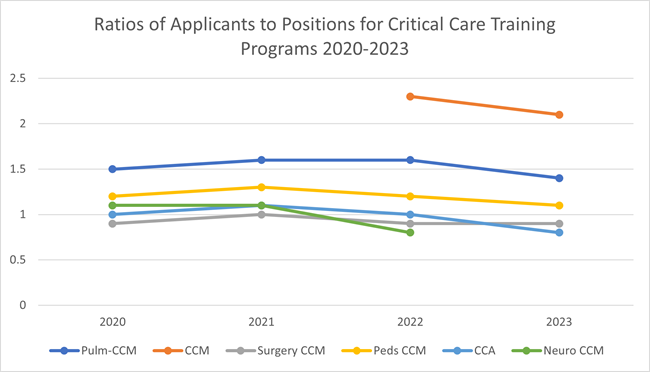

The ratio of applicants per position has remained steady across all training programs with the increased number of open positions available, highlighting the continued and reliable interest in critical care medicine. A notable finding is the higher ratio of applicants per position for the newer, stand-alone critical care medicine training programs (

Figure 2). This contrasts with the more conventional intensivists who have training and work in other specialties of medicine and will hopefully lead to increased numbers of highly trained and capable critical care physicians.

Figure 2: Applicants per Position for Different Training Programs

CCA, critical care anesthesiology; CCM, critical care medicine.

Data compiled from: National Resident Matching Program4 and SF Match.3 |

According to data from the American Association of Medical Colleges, there has been an overall increase in critical care physicians, from 13,093 in 2020 to 14,159 in 2022. A smaller increase occurred in pediatric critical care physicians in that same time period, from 2639 physicians to 2774.

5 Both of these increases lowered the ratio of patient per physician in both adult and pediatric critical care (

Figure 3). The continued rise in critical care physicians will be beneficial for a continuously aging population and the increasing need for critical care services in the United States. The trends appear favorable in all aspects of critical care training. Continued recruitment of residents into critical care medicine will be vital to the field.

Figure 3: Total Physicians Across Critical Care Medicine and Patient-to-Physician Ratios, 2020-2022

CCM, critical care medicine.

Data from Association of American Medical Colleges.6 |

|

Growth in Critical Care Pharmacy Programs

Critical care pharmacists perform numerous direct patient care activities including evaluating, monitoring, and managing drug therapies; screening and addressing drug interactions and potential adverse events; and completing medication histories. The PHarmacist Avoidance or Reductions in Medical Costs in CRITically Ill Adults (PHARM-CRIT) study evaluated critical care pharmacist interventions and the subsequent impact on cost avoidance and reduction in medical costs in critically ill patients.

7 The most common interventions were adverse drug event preventions, resource utilization, individualization of patient care, prophylaxis, hands-on care, and administrative/support tasks. The investigators found that that the annualized cost avoidance from a critical care pharmacist was $1,784,302, which correlated with a potential monetary cost avoidance-to-pharmacist salary ratio between $3.3:1 and $9.6:1.

7

The conventional pathway to becoming a critical care pharmacist requires a doctor of pharmacy degree, two years of postgraduate clinical residency training, and board certification in critical care pharmacotherapy. Residency training includes a PGY1 general pharmacy residency followed by a PGY2 residency in critical care. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Resident Matching Program data shows continued growth in available critical care PGY2 programs and positions.

8 In 2019, there were 143 programs with 189 positions available; in 2023 these numbers increased to 173 programs with 223 positions available. After completing a PGY2 residency in critical care, pharmacists can sit for the board certification examination in critical care pharmacotherapy. Between 2016 and 2020, the number of board-certified critical care pharmacists increased from 532 to 2873. This number is projected to reach nearly 5200 by the year 2025.

Despite this consistent growth, the number of board-certified critical care pharmacists remains relatively low when considering the number of intensive care unit (ICU) beds reported in the United States. While there is a recommended practitioner-to-patient ratio for intensivists (1:14), there is no recommended pharmacist-to-patient ratio, although the consensus is approximately 1:15.

9 Recent surveys have shown that many critical care pharmacists report ratios higher than this, even as high as 1:30.

9 The gap in critical care pharmacist services has been described as a significant and underappreciated public health concern.

10 Multiple factors have led to the lack of critical care pharmacists, including pharmacy budgets, insufficient number of residency programs/positions, lack of compensation for services provided, and no minimum staffing regulations from major accrediting bodies. Ultimately, there is a need for an increased number of PGY2 critical care residencies, an increased incorporation of critical care pharmacists on every multiprofessional care team, and development of compensation strategies for services provided by critical care pharmacists.

Growth in Critical Care Advanced Practice Programs

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) are collectively identified as APPs. There continues to be projected growth of APPs in critical care to help meet demand and to alleviate physician shortages.

11 As these roles have evolved, efforts have been made to bridge the gap between education and practice by professional organizations for both NPs and PAs.

The lack of demographic data for critical care APPs makes it challenging to identify the current state of the critical care workforce and to predict future demands, trends, and potential workforce gaps. The 2022 Bureau of Labor Statistics has estimated that there are about 30,000 NPs currently practicing in critical care.

12 According to the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants’ (NCCPA) 2021 statistical profile of certified PAs by specialty, approximately 2071 PAs identified their primary practice as critical care medicine and 144 identified it as pediatric critical care medicine. However, this likely underestimates the number due to PAs identifying with their department rather than their practice setting (i.e., surgery or anesthesia).

12

In their Vision for Academic Nursing white paper, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing highlighted the transition to competency-based education and increased collaboration between education and practice (developing formal academic practice partnerships) as crucial initiatives.

13 Multiple agencies worked together to create criteria to update standards and facilitate NP program quality and ongoing quality improvement initiatives, which include efforts to increase postgraduate fellowship/residency programs. The American Nurses Credentialing Center offers accreditation for NP fellowships and registered nurse (RN) fellowships/residencies; a total of 249 programs (advanced practice registered nurse/RN) are currently accredited. The Consortium for Advanced Practice Providers was developed to offer support for NP/PA postgraduate training programs. The consortium lists 46 postgraduate NP/PA training programs under the labels of acute care or critical care/emergency medicine.

The Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant (ARC-PA) began the accreditation process for postgraduate clinical programs. A total of 15 postgraduate clinical programs have been accredited by the ARC-PA, with two programs specifically in critical care medicine, although the Association of Postgraduate PA Programs lists a total of 16 critical care medicine PA residency programs. The 2021 NCCPA survey identified 249 PAs who had completed postgraduate training in critical care.

Growth in Nursing and Nurse Residency Programs

To grow and improve training for new graduate nurses, nurse residency programs are implemented across the United States. One-year nurse residency programs are designed for new graduate nurses to facilitate their transition to professional roles in a stimulating and fast-paced healthcare environment. Many of these programs are based in academic medical centers, and the nursing staff in these units treat complex cases and provide specialized care not offered at outside referring facilities. Key threads throughout the program include critical thinking, patient safety and minimizing risk, leadership, communication, research-based practice, and professional development. These programs have been shown to help with retention of nurses and can also provide a pathway for advancement in a specific area of interest.

Growth in Respiratory Therapy Programs

As with many other areas of healthcare, the number of practitioners in respiratory therapy is declining. RTs are crucial members of the critical care team, and their continued involvement is paramount for optimal care of critically ill patients. Unfortunately, the number of graduating RTs will not be able to meet the numbers of RTs leaving the profession, mainly due to retirement. Burnout from the COVID-19 pandemic has also pushed some to leave the field and retire early. It is estimated that 92,474 RTs will leave the field by the year 2030. Compounded with the decline in enrollment in RT programs by 27% since 2010 and full enrollment in only 10% of programs, this leaves a massive hole to fill and one that may be difficult to remedy.

14

To retain and recruit RTs, investments in technology and innovations in common procedures must be considered. Innovations in mechanical ventilators and investments to improve patient care procedures (e.g., arterial blood gases, aerosol therapy, bronchoscopy) were all reported as vital to the success and retention of RTs in the future.

14 The American Association for Respiratory Care is currently spearheading the recruitment effort with outreach to promote the field.

Effects of the Pandemic and Burnout on the Critical Care Workforce

The COVID-19 pandemic brought many changes to the delivery of critical care, but one long-lasting impact is persistent practitioner shortages throughout the healthcare system.

15 Almost 100,000 RNs left the profession during the COVID-19 pandemic and an estimated 800,000 intend to follow by 2027.

16 A national study of 20,665 U.S. healthcare practitioners found an attrition rate of 2 in 5 for nurses and 1 in 5 for physicians leaving their practice altogether.

17 Fear of exposure/transmission (OR, 1.29; 95% CI 1.18 to 1.42), burnout (OR 2.15; 95% CI 1.93 to 2.38), being in practice longer than 20 years (OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.46 to 1.76), and anxiety/depression (OR 1.25; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.39) were all significantly associated with intent to reduce work hours and leave their practice within the next 24 months. Turnover was highest among health aids and assistants, followed by licensed practical nurses and licensed vocational nurses.

18

This shortage is especially prevalent in critical care, with an estimated 27% of critical care nurses leaving the profession worldwide,

19 reflected in unstaffed ICU beds, ongoing delays in delivery of patient care, and increased work burden on critical care practitioners. Protective measures must be implemented to address staff well-being, increase resilience, and provide a safe and supportive work environment in order to reduce burnout and retain our most valuable assets—our healthcare practitioners.

While filled with the joys of caring for patients and families in the ICU, critical care medicine is also filled with many challenges and stressors. Burnout in critical care has always been higher than in other specialties, and the COVID-19 pandemic brought to light additional stressors that challenged even the most resilient practitioners. An estimated 35% to 45% of nurses and 40% to 54% of physicians in the United States have burnout, with U.S. intensivists experiencing the highest burnout rates, at 25% to 71%.

20

Conclusions

Career prospects for future critical care health professionals remain strong; continued recruitment and training is needed to maintain the workforce necessary for high-quality patient care. Multiprofessional teams have been shown to have the best outcomes when it comes to critical care practice, and continued training and work to create these teams and practice models should be undertaken. Healthcare systems must commit to offering opportunities to train the critical care workforce, an excellent recruitment and retention strategy. Healthcare systems must also commit to changes that address burnout, moral injury, and other causes of practitioner attrition. Collaboration and utilization of SCCM resources is an excellent start.

Lead author Shaun L. Thompson, MD, discussed this article and appraised the ICU workforce pipeline, including how it will affect future healthcare needs, during the 2024 Critical Care Congress. Watch the session on YouTube.

Contributing Authors: Quinton B. Behlers, PharmD, BCCCP, MPH; Ambadasu Bharatha, PhD, MSc (med); Megan M. Blais, PharmD, BCCCP; Sigrid Burruss, MD; Lyndie Farr, ACNP, DNP; Kandamaran Krishnamurthy, MD, FCCM; Michelle Linderman, RN; Emily M. McRae, DNP, APRN, CPNP, FCCM; Jeffery M. Nicastro, MD, FCCM; Kalpana Norbisrath, MD; Kristin Passler, RN; Michelle M. Ramirez, MD; Kathleen P. Thompson, MPAS, PA-C.

References

- Khanna AK, Majesko AA, Johansson MK, Rappold JF, Meissen HH, Pastores SM. The multidisciplinary critical care workforce: an update from SCCM. Crit Connections. 2019;18(2):23-26.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: Specialties Matching Service 2023 Appointment Year. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, DC. 2023.

- SF Match. Residency and Fellowship Matching Services. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://sfmatch.org/specialties

- National Resident Matching Program. Main residency match data and reports. 2023 main residency match. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/match-data-analytics/residency-data-reports/

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician Specialty Data Report. 2022. Accessed September 21, 2023.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician Workforce Projections. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2019 to 2034. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/complexities-physician-supply-and-demand-projections-2019-2034

- Rech MA, Gurnani PK, Peppard WJ, et al. Pharmacist avoidance or reductions in medical costs in critically ill adults: PHARM-CRIT study. Crit Care Explor. 2021 Dec 10;3(12):e0594.

- National Matching Services, Inc. ASHP Resident Matching Program. For residency positions beginning in 2024. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://natmatch.com/ashprmp/

- Newsome AS, Smith SE, Jones TW, Taylor A, van Berkel MA, Rabinovich M. A survey of critical care pharmacists to patient ratios and practice characteristics in intensive care units. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020 Feb;3(1):68-74.

- Sikora A. Critical care pharmacists: a focus on horizons. Crit Care Clin. 2023 Jul;39(3):503-527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2023.01.006

- Kleinpell RM, Grabenkort WR, Kapu AN, Constantine R, Sicoutris C. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in acute and critical care: a concise review of the literature and data 2008-2018. Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct;47(10):1442-1449.

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Statistical profile of certified PAs. 2021 annual report. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.nccpa.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2021StatProfileofCertifiedPAs-A-3.2.pdf

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. AACN’S vision for academic nursing. Executive summary. January 2019. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/0/PDFs/White-Papers/Vision-Academic-Nursing.pdf

- Miller AG, Roberts KJ, Smith BJ, et al. Prevalence of burnout among respiratory therapists amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Respir Care. 2021 Jul 16;respircare.09283.

- Martin B, Kaminski-Ozturk N, O'Hara C, Smiley R. Examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on burnout and stress among U.S. nurses. J Nurs Regul. 2023 Apr;14(1):4-12.

- Muoio D. About 800,000 nurses planning to leave the profession by 2027, data show. Fierce Healthcare. April 14, 2023.. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/providers/about-800000-nurses-planning-leave-profession-2027-data-show-0

- Sinsky C, Brown R, Stillman M, Linzer M. COVID-related stress and work intentions in a sample of US health care workers. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021 Dec;5(6):1165-1173.

- Frogner BK, Dill JS. Tracking turnover among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Health Forum. 2022 Apr 8;3(4):e220371.

- Vogt KS, Simms-Ellis R, Grange A, et al. Critical care nursing workforce in crisis: a discussion paper examining contributing factors, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and potential solutions. J Clin Nurs. 2023 Oct;32(19-20):7125-7134.

- Niven AS, Sessler CN. Supporting professionals in critical care medicine: burnout, resiliency, and system-level change. Clin Chest Med. 2022 Sep;43(3):563-577.